Some of what I have found in my creative journey with PIA is courage I didn’t know I had, learning to trust creative flow, trusting myself to let go of knowing, deeply opening to not knowing, and creating space to nourish my creativity. We are on this immensely diverse, creative planet for such a short time; I hope you will take advantage of the creative gifts you have to bring forth.

—Nicolee McMahon, Roshi, Co-founder, Three Treasures Zen Community, San Diego, California

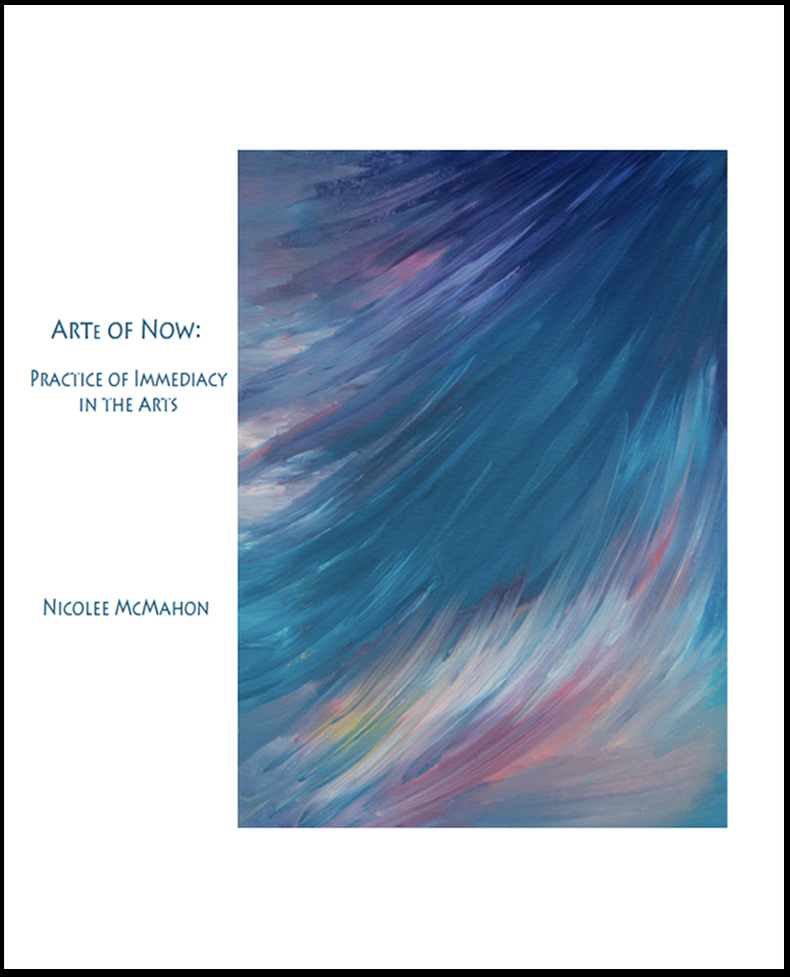

The beauty of Nicolee McMahon’s Arte of Now: Practice of Immediacy in the Arts lies in the wisdom of creativity itself, a wisdom demonstrated 30,000 to 40,000 years ago when Homo sapiens painted prehistoric rock art (parietal art) on the walls of caves. Realistic and extinct animals, handprints, abstract dot paintings, and geometric shapes graced the cave walls, evidence that our ancestors had evolved a brain capacity that began at least 200,000 years ago. Neuroscience shows that humans are “wired to create” and use their whole brain to do so. As scientists discover more about the brain and creativity, humankind’s need to create is abundantly clear: The urge is expressed everyday through art, music, dance, theater, film, and the written and oral word from the very young to the very old.

Wherever humankind has made its mark, it is through the creative force—an incredible ability that can take your breath away. And into this world of creativity-making Nicolee McMahon has stepped fully equipped with the philosophy, history, and practice that can transform an interior creative landscape inside out.

PART ONE: PRACTICE OF IMMEDIACY IN THE ARTS

THE PHILOSOPHY of PIA

In the epigraph to Arte of Now: Practice of Immediacy in the Arts, McMahon quotes Dogen Zenji, from a section of “Uji” (Being-Time): “The way the self arrays itself is the form of the entire world. See each thing in this entire world as a moment of time. Things do not hinder one another, just as moments do not hinder one another. The way-seeking mind arises in this moment . . . .” McMahon grounds Arte of Now: Practice of Immediacy in the Arts (PIA) on her Zen practice of meditation, which “allows us to realize the interrelated unity of everything. Seeing this oneness, we realize that nothing is missing, and the uniqueness of each moment is inherently equal to the next.” As in the epigraph above, experiential PIA allows a flow to unfold, in which “one opens to not knowing—an open and nonjudgmental mind space that lets go of opinions, views, concepts and desired outcomes.”

Whatever arises is without judgment and is good enough, as Arte of Now does not journey in supposition, preconceived ideas, or plans that compromise the process. It is a “letting go” in the act of doing, trusting the process, and by “including everything, an innate spaciousness and a creative flow can emerge.” The key is the practice itself, as it reveals “the interrelated unity of everything.” It is the “cacophony of now.”

THE HISTORY of PIA

A Zen teacher and artist, McMahon had spent years experimenting with an as yet unnamed practice with her artist materials in her home studio. She thought about introducing the practice into her Zen retreats, but somehow considered such an introduction “taboo,” as if she would be crossing a line. During a weeklong retreat, however, she was working with a variety of materials when the overwhelming fear she had felt about introducing the practice “showed up, and what unfolded was a structure with eyes staring down hard on a meditation hall scene. Following a creative flow, I added a goofy figure with rotating yellow and blue eyes looking around the wall of the meditation room, and the spell was broken.”

The creative energy McMahon experienced at the retreat allowed her to step outside the norms of the retreat environs and to speak of what she had felt—a creative flow that knew no bounds. It was process without a destination. She gave this creative energy a name: first, “spontaneous expression,” and then “practice of immediacy in the arts”—an unhindered flow of creativity from within and without.

Voice of PIA

Although the creative flow was open to her, she wanted to try a method that she had learned called Voice Dialogue, in conjunction with PIA. With Voice Dialogue, she could get in touch with different “internal voices,” such as the voice of the “inner critic.” Her purpose was to hear “the voice of PIA speaking for itself without filters.” Using Voice Dialogue, she transcribed the voice of PIA in two different sessions as it spoke to her (both transcriptions are reproduced on pages 23 to 25). Having “struggled to find words about the practice of immediacy that would make sense to others,” she found that “the words of the voice of PIA captured what I had not been able to articulate.” She was now ready to share her experience and the insights gleaned. (McMahon clarifies that PIA does not require knowledge of Voice Dialogue.)

In a brilliant move, McMahon arranged the longer transcriptions into smaller stanzas but retained the sequence of the voice of PIA. Then, she paired a stanza with each of the paintings reproduced in Part Two of the book (see discussion below). Thus, the voice of PIA, as rendered in stanzaic form, accompanies each painting. The synergistic effect is one of immediate awareness.

PART TWO: PRACTICE OF IMMEDIACY IN THE ARTS (PIA) — VISUAL EXAMPLES

Arte of Now is not only a book of instruction in the practice of immediacy in the arts, but it is also an art book. Part Two comprises twenty-five reproductions of art that McMahon painted over a period of seventeen years as she developed PIA. (It also includes six reproductions of the work of other artists.) Each painting is titled and accompanied by a stanza excerpted from the voice of PIA as discussed above.

“Light,” PIA acrylic on canvas, is the first reproduction in Part Two. The stanza that accompanies ‘Light’ is from the “First Day” transcription of the voice of PIA:

I flow through all media

Expressing

Fleeting moments of Now

That can’t be grasped

———gone

each moment of time

dissolved,

These twenty-five reproductions of McMahon’s art, including the book cover painting “Wings,” accompanied by the words of the voice of PIA, show not only the creative promise of Arte of Now but point also to the inherent value of seeing the interrelated unity of everything.

PART THREE: HOW TO DO PRACTICE OF IMMEDIACY IN THE ARTS

DIRECTIONS

Having gained a depth of knowledge about PIA in her home studio, she introduced it at meditation retreats and to other artists, writers, and musicians. In honing PIA through this personal study and public observation, McMahon found that five directions are essential to the practice of PIA:

Select Creative Medium and Materials You Want To Work With

“Choose a medium such as “art (e.g., pastels, colored pencils, painting, drawing, collage, sculpting), musical instrument, voice, writing, crafts (e.g., beading, wood construction, fabric), or dance/movement, etc.”

Open To Not Knowing

In Dogen Zenji’s epigraph mentioned above, he states: “A way-seeking moment arises in this moment. A way-seeking moment arises in this mind.” In the practice of PIA, McMahon renders this Zen “way-seeking moment” into being “open to not knowing,” advising you to “come from an attitude of openness, not planning your project or attempting to know in advance what it will look like.” This is the step through which the “way-seeking moment arises.”

Include And Express What You Are Aware Of As It Shows Up

In this step, McMahon advises you to express your awareness of sounds, sensations, smells, and touch in your environment through the medium and materials you have chosen to work with. Include everything, she urges: “the smell of food cooking, thoughts, the sound of birds chirping, cars going by, memories, body sensations from the hardness of chairs, emotions, sunlight, a taste in the mouth.” Let whatever you are feeling, sensing, and thinking be expressed in the medium you have selected.

Express Expectations As They Are Occurring

Most likely, you will be curious about what will happen during your practice of PIA and what the end result will be. McMahon’s advice is to include any and all expectations as they emerge however you define, describe, or identify them. Expectations that might arise “include ideas about any kind of ‘spiritual’ or ‘wisdom’ attainment, as well as ideas about creating something attractive, original, beautiful or deep.” They are “part of the flow”—even an expectation of resistance.

If You Enter A Creative Flow, Follow Its Unfolding

McMahon describes this step as an experience of “being carried along by a creative wave or current that may have a certain energetic feel to it,” one “that directs you towards certain media, forms, textures, and colors.” The end result or expression might not be what you expected or hoped to realize, but McMahon advises that whatever the expression is, the flow is in service of “not knowing in action.”

SAMPLE SESSION

In this section, McMahon demonstrates the steps in a practice session of PIA. Choose a medium, she instructs, such as paper and oil pastel crayons. Open yourself to “not knowing” and begin to express through this medium what is happening in your environment. “Perhaps you are aware of the hardness of the seat of your chair,” she suggests, and you “select a pastel color and give shape to the experience any place on the paper—maybe it’s a thick straight line.” You continue to express what you are aware of, such as a car going by or “the whizzing of a hummingbird” and use “the oil pastel to give color, shape, form or texture to what is present.” Express inclusively these moments of awareness, as well as your judgments, ideas, memories, even your awareness that you are performing. Nothing is rejected; everything is included during the practice until the end of your session. Videos demonstrating Practice of Immediacy in the Arts are available here.

PART FOUR: REVISED PRACTICE OF IMMEDIACY IN THE ARTS (PIA+): VISUAL EXAMPLES AND POEM or REVISED PIA (PIA+)

Part Four comprises ten reproductions of what McMahon calls “revised PIA (PIA+),” an extension and expansion of PIA. Whereas in PIA you are open to the flow of your creative energy, PIA+ constitutes “editing, revising, changing” the original piece you worked with while in PIA mode. In each of the ten reproductions that appear in Part Four, McMahon explains how she reworked the original PIA painting. For example, the second reproduction in this section is titled “Shaman’s Dream.” How she arrived at this painting (PIA+) is a testimony to the intuitive nature of creativity.

“Shaman’s Dream,” McMahon explains, began as PIA, unplanned with no destination in mind. She didn’t like it, so she put it aside and began another PIA. When she finished the second PIA, a serendipitous moment occurred: She used the first canvas to clean her brushes. Later, she looked at this canvas again, and saw something in it that surprised her. “The canvas began to have a life that wanted to be seen,” she writes. Then, she took up her brushes and “painted black where I felt it belonged and began to see birds flying and a shaman in the lower part of the canvas.” Perhaps her training with a medicine woman during this time had inspired her in this direction. She completed “Shaman’s Dream” in 2004 in the middle of the training.

CONCLUSION

It isn’t happenstance that Nicolee McMahon’s insight into Dogen Zenji’s teaching on Being Time was an essential part of her liberating the creativity within herself. This insight, she writes, contributed to her “understanding of the nature of life and the transformative power of practicing with each moment as inherently equal, whole, and complete.” It was many years later, when PIA was unfolding, that she realized Dogen Zenji’s teachings on Being Time was also an essential element of PIA. Once McMahon saw how PIA could inspire creativity using the five directions and the voice of PIA she could share it with others. Arte of Now: Practice of Immediacy in the Arts is the culmination of her “creative exploration and expression” and her gift to everyone living on our diverse and creative planet.

1 comment

Nicolee McMahon is a master of many disciplines and it is wonderful to see her bring forth a way for her readers to tap into some of her expertise. This book is the result of her many years as an artist, therapist, and Zen teacher, bringing forth a practice which is suitable for everyone regardless of age or experience. I hope many people will get a chance to read this book and then put into practice her invaluable teachings.