As a life-long pursuit, education as the acquisition of knowledge never ends. It is always present in our daily lives, as a cumulative effect of years of study or research, or as an “aha” moment that brings enlightenment and joy.

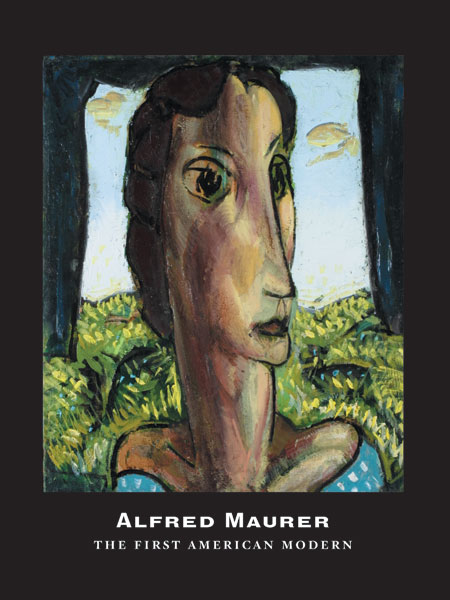

Such is the “aha” moment I experienced when I first read and then studied Daphne Anderson Deeds’essay, Alfred Maurer: The First American Modern. Would I be overstating this “aha” moment, the enlightenment and joy I felt, as well as the knowledge I gained, after reading this essay? Not at all, for several reasons. First, this essay took me outside my literary comfort zone and challenged me to understand art, specifically, Alfred Maurer’s art, from an art historian’s perspective. Second, it forced me to research terminology, such as “modernism,” “impressionism,” “fauvism,” “cubism,” and “expressionism,” in order to appreciate the essay. I know the words and their general meaning from having seen many art exhibitions on modernism, but did I really understand their importance in the context of Alfred Maurer’s art? Third, Deeds—a fine art consultant and art museum professional—writes authoritatively, as would be expected, given her experience curating more than seventy exhibitions and publishing more than fifty art catalogues and articles. Given this impressive record, readers might ask themselves this question before reading the essay: Would it be beyond their grasp? My advice is—have no fear! Not only does Deeds educate her audience about modernism, fauvism, impressionism, and every “ism” Maurer tried in the forty-plus years of his artistic life, but she also connects with readers in a style that is both erudite and accessible.

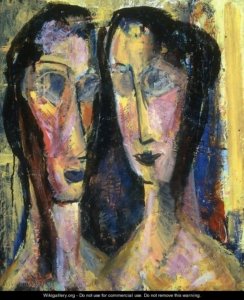

For example, in describing one of Maurer’s double portraits Two Heads (1928-30) as “an irregular rhomboid shape,” Deeds explains what is happening in the painting: “The horizontal traversing the upper quadrant of the picture further emphasizes the verticality and creates a box-like framework that is superimposed over the composition.”[1] As I read this sentence and studied the painting, I saw the horizontal in the upper quadrant and the verticality she references, and then the “aha” moment came: I saw the boxlike framework superimposed over the figures and the entire composition. In this way, Deeds taught me how to experience Maurer’s Two Heads and the other double figures in his oeuvre.

Alfred Maurer: The First American Modern is the title of Deeds’ essay and the catalogue that accompanied the Maurer exhibition, which traveled to the Georgia Museum of Art in April 2003 and to the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, in September 2005, stopping at four national museums in the interim two years. As the host of the traveling exhibition and owner of a permanent collection of six hundred forty-four paintings and works on paper by Maurer, the Weisman Art Museum had two specific goals: to further the recognition of the artist’s contribution to American modernism and to “help foster a new appreciation of his talent by scholars and museum visitors alike.” [2]

Alfred Maurer did not go entirely unnoticed during his artistic career from the 1890s to the early 1930s, but it was not until many years after his death in 1932 that he began to receive the critical attention that he is now granted. After all, he was the first artist to introduce Fauvism to the United States when he returned from Paris in 1914 on the cusp of World War I. During his seventeen-year sojourn in France, he assimilated the innovative and experimental techniques of his mentors Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. Although he never studied with Matisse, Maurer took to heart the subjective tendencies of Fauvism and asked himself: What did he want to paint? What was inside him? He embraced Matisse’s aesthetic, Deeds explains, enjoying the release in vibrant colors, a sense of movement, and personal expression. “Color seemed to liberate him, allowing him to escape the prescribed world he had left behind in America,” Deeds writes. [3] The transition he made during the Parisian years between 1905 and 1914 can be seen in the contrast between his 1909 painting Landscape With Trees—his Matisse-inspired work—and the academic portrait of his sister Eugenia, (Eugenia, 1896-1897), painted more than ten years earlier.

Why the indifference to Maurer during his lifetime? According to Deeds, critical reaction has been attributed to his stylistic changes and lack of consistency over a sustained period of time; indeed, he avoided “convention and relentlessly challenged himself to pursue a personal expressionism that was both advanced and bewildering.” [4] Although he was invited to show his work at group exhibitions, it was not until after his death in the mid-1930s and 1940s that critics began to assess his contributions to modernism. In the intervening twenty or thirty years, however, Maurer was largely unknown to major museums, and it wasn’t until 1973 when the Smithsonian American Art Museum (formerly the National Collection of Fine Arts) in Washington, D.C., organized a retrospective exhibition of his work. [5]

As a scholar of modernism, and specifically of Alfred Maurer, Deeds offers a perceptive counterpoint to the oft-stated reason why Maurer was disregarded for so many years. In fact, she points out, “his endless searching and experimenting with myriad methods and styles may in fact provide a key to the nature of this lonely and ultimately tragic figure.”[6] She admits reluctance to interpret an artist’s work through biography, but “in the case of Maurer” she “cannot avoid exploring the facts of his life.” [7]

His personal history and his work are so intertwined that “his often obscure career is rendered more coherent when we consider the experiences that may have motivated this peripatetic artist and his often tortured soul.” [8] Accordingly, Deeds lays out the biographical details that support her argument.

Maurer’s father was a domineering presence in his son’s life. Both a skilled lithographer and a prominent illustrator for Currier and Ives, Louis Maurer forced his sixteen-year-old son to quit high school to work in the family’s lithographic-printing firm, expecting young “Alfy” to follow in his footsteps. Taking classes at the National Academy of Design for twelve years until 1897, the year he left for Paris, Maurer began “experimenting with non-representational color” and “embracing modernist innovations.” [9] In spite of his father’s overbearing personality, Maurer moved into his parents’ home when he returned from Paris, and he lived with his father for the rest of his life. “Even…in middle age, he was unable to defend his work or to extract himself from his demeaning living situation,” Deeds observes. [10]

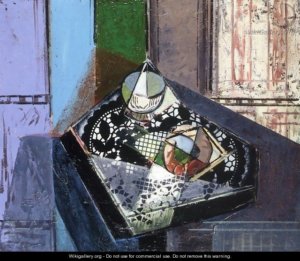

In spite of his father’s scorn toward his modernist work—he ridiculed it at every turn—Maurer continued to experiment and pursue innovative methods that produced paintings as different from each other as his “sad girls”; his collages, such as Still Life with Cup, which Deeds calls “some of the most sophisticated paintings in his oeuvre” [11]; and his nudes, specifically The Contortionist, an unusual rendering of a nude woman executing “a limber handstand on a pedestal.” [12]

Between 1928 and 1930, Maurer began to paint portraits of women with long necks and haunting eyes, which “provide a tantalizing and disturbing glimpse of the artist’s final creative efforts.” [13] In the painting Head of a Girl (1929), pictured on the cover of the catalogue, Deeds describes the girl’s haunting eyes as seeing “beyond the picture plane and into an existential void.” She asks, “Do they belong to the sitter, or are they Maurer’s?” [14]

In Maurer’s final years, he returned to the “twin theme” he had painted earlier. In Two Heads with Yellow Background (1928-29), “the two figures are joined at the shoulders and by their hair.” [15] Between them is a “dark void.” Interpreting this painting as expressive of Maurer’s inner existential darkness, Deeds suggests that the real subject of the painting isn’t whether it is about two women or one women, but about Maurer’s “contemplation of the Other.” She writes: “Questions about how one person can communicate with another, how one person perceives another, and how all people are ultimately unknowable were no doubt on the mind of this lonely and by now almost completely isolated man.” [16] While Maurer was failing in his artistic career in the late 1920s and early 1930s, his father was being celebrated for his artistic legacy—folksy Americana versus inscrutable modernism. It was a double blow to the son. In February 1932, Louis Maurer celebrated his one-hundredth birthday and died five months later. Alfred Maurer turned sixty-four in April of that year. Less than a month after his father’s death, Maurer hanged himself in his room on the third floor.

What should we make of this tragic figure, who, according to Deeds, was experimenting with early modernist methods and styles before any other artist in America, and whose work preceded the abstract expressionism movement by a decade or more? [17] Critics vie in their opinions of Maurer: Did he lack the temperamental strength to solve the difficult issues surrounding his work, thereby eclipsing his legacy as one of the greats in the American pantheon? Or was he a brilliant artist whose “introverted modernism is celebrated as a quintessentially American vision”? [18] There is no doubt that Maurer pursued his own vision, even as he was plagued by demons he could not reconcile in his mature years. He did not claim to belong to one particular movement or school of thought, although his oeuvre spans the various “isms” of the early modernist period. In my opinion, no other American artist can claim the brilliance of The Contortionist. And whatever critics may think of his work, no other artist can claim the title of “the first American Modern” either.

2 comments

Wow – very educational and truly appreciated.

Thank you, Glenn, for your comment. Yes, Daphne Deeds’ essay is erudite, accessible, and a brilliant take on Alfred Maurer. We who are not trained to “read” art can learn from art historians like Daphne. They can teach us much, as I did with her essay, Alfred Maurer: The First American Modern. I became quite fascinated with his paintings, especially The Contortionist and Two Heads.