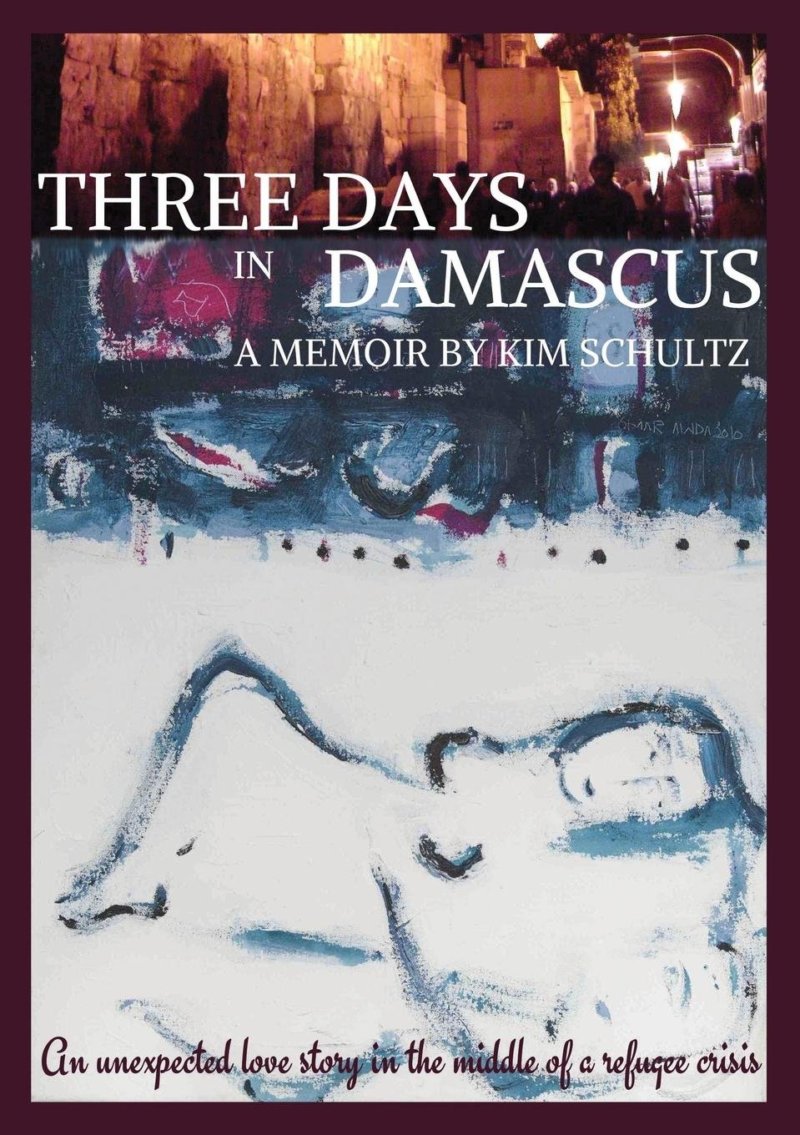

Sometimes a trip can unexpectedly mean more than a visit to a historic place, a flight to a coveted conference overseas, or a vacation to your favorite spot on a remote island. In the extreme, a trip can become an existential, life-altering experience that changes your sense of yourself and the world around you. Such was the kind of trip that Kim Schultz—writer, actor, playwright—took in 2009 to Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria. Accepting an invitation by the NGO Intersections International as a member of a multi-disciplinary group of artists whose purpose was to interview Iraqi refugees in the Middle East, Schultz was unprepared for what happened. She fell in love with Omar, an Iraqi refugee, at the end of the month-long trip and wouldn’t see him again for three years.

You could divide Three Days in Damascus, Schultz’ absorbing memoir, into two different awakenings—pre- and post-Damascus—both of which presented her with existential questions: Who am I? What am I made of? Why am I here? To try to answer which awakening was more consequential rings of a false equivalency, as each one—pre- or post—was different in form and content. The post-Damascus awakening could not have happened without a pre-Damascus period; the latter was the reason she had gone to the Middle East in the first place. Rudely awakened to the reality of the Iraqi refugees who had fled the ever-evolving tragedy in Iraq, she felt their suffering deeply, an experience she couldn’t shake or rationalize. This pre-Damascus awakening encompassed her body and soul, as she faced the inconsolable loss the Iraqi refugees had suffered. Schultz wrote plays and built characters out of words, but here were flesh and blood Iraqi women, men, and children whose lives she would eventually render in No Place Called Home: This Isn’t Supposed to Be a Love Story as part of the deal with Intersections International. Omar became the central character in this play.

By the time she met Omar three days before she was to leave Damascus, Shultz had interviewed Iraqi refugees in several Middle Eastern countries after they fled Iraq. In Beirut, Lebanon, Schultz met Saleema, an older woman in her sixties or seventies, and her husband Dauod, a diabetic, who sold alcohol. They were forced to leave Iraq because, as Saleema told Schultz, “they” destroyed their home, their church, and neighborhood. At the Beirut Center for Women and Children, four Iraqi children had lost their mother but they didn’t know exactly how; maybe she was “kidnapped or ran away or was killed or something.” Schultz couldn’t get a straight answer from them, but she saw in their vacant eyes that they had stopped thinking about the future; they didn’t dare to dream. Then there was Sawssan, who had “a certain faded beauty about her.” Her brother-in-law was killed in the car her husband drove for the United States government and more bullets missed her husband by inches. Her six-year-old son Youssef didn’t speak, except at night when he sang a prayer, “the only thing he [could] now safely offer the world.”

When she arrived at the Refugee Center in Amman, Jordan, Schultz listened to more affecting stories like those she had heard in Beirut. In Amman, she met Raheel in the alleyway, smoking. He told her he needed to get to Iowa in the U.S. where his whole family was, but he had been denied refugee status because he was a twenty-three-year-old male and had a bad leg. Tears streaming down his face, he wanted to know why America couldn’t take him, and he questioned what kind of America would leave him behind. Schultz took his name but she could do nothing for him, nothing at all. Then she met Mona, the practically dead woman, “her bones look[ing] heavy with grief. She told Schultz that both of her brothers were killed by the United States and the U.S. had sent a letter of apology. “‘You wish to see the letter?’” Mona asked Schultz. Schultz writes in her memoir, “Two brothers, both dead, both by the United States of America—be it by a miscalculation, misdirection, or misjudgment. U.S.: 2. This family: O.”

Damascus was the last leg of her trip, and the pathos of psychological and physical injury pervaded every interview there, as it had in Amman and Beirut. In Damascus she met “smiling” Sarah who lived in an upscale apartment—relatively speaking— with her children. Sarah told Schultz her story: She and her husband had to seek medical attention outside Iraq because a car bomb had injured him, paralyzing half his face. Before he could be helped, he had to return to Iraq when his mother became ill. She hadn’t heard from him in a year and pretended to speak to him on the phone so her children wouldn’t know he was dead. Sarah was “afraid to tell them the truth . . . to tell them to no longer wait, that he is not . . . coming home.” After hearing Sarah’s story, Schultz lost it. The tears came, and by the time she reached the balcony she was sobbing, remembering as if in a visual flash the cinder block family, “Saleema and Daoud, Raheel, Hatm, the blue shirt man and Najah and her already dead children. And of course Fakher, always Fakher. They were all around me—dancing, sobbing, waiting.”

In Damascus, Schultz was reeling because of the endless suffering; she felt like she was “drowning in helplessness and heartache.” Late in the afternoon on one of those exhausting days, a grandmother read Schultz’ “coffee grounds,” like a fortuneteller reads a fortune. Certainly, it was not a straight line between the coffee grounds and the man Schultz would meet at a social event for artists that same evening. No one can posit a cause and effect between the coffee grounds and Omar, but there was such an intense reaction between the New Yorker and the Iraqi refugee at this gathering you might be justified in believing the coffee grounds had something to do with the “look” they gave each other. It seemed as if it couldn’t have happened any other way. After all, the grandmother told her she was going to meet a man, maybe even in Damascus.

Schultz was more than ready to leave Damascus to return to her apartment in New York City, but then she met Omar. The connection between them was “immediate, intense and impossible.” The coffee grounds were foregrounded: Was he her “coffee ground man?” She was thirty-nine years old and had never met a man who captivated her like Omar did. He invited her to see his paintings and gave her his card. The next night at his apartment, she was relieved to see that he could really paint—“bright, suggestive, aching, plaintive, rich and racy” with lots of boobs. Still, she questioned her judgment: What was she doing in an Iraqi man’s apartment, a man she hardly knew, alone, trying to concentrate on his art, but also aware that she was inside a “magnetic field,” their bodies close, their “arms almost touching,” her “hair brushing his shoulder,” a “gentle hand sweep.” Omar led, and she allowed herself “to be suspended in the time warp” she found herself in—“the misty, magical, sensual suspension of time, in an old-world country with my old-world Omar.”

Thus began a run-a-way romance just days before she was to return to a normalized life in New York; that is, to her life before she was awakened to the despair of refugees fleeing war in their home country. When she said good-bye to Omar the night before she left, Kim Schultz wanted to tell him that she had fallen in love with him. He said, “Shh . . . Say nothing, habibti [my love]. There is nothing to say.” Disconcerted, she thought:

How can he say that? There is so much to say. I want to say how

this has been the most amazing three days of my life; yes, I know

it’s only been three days but I think we have something here, that

I want to come back and visit him again or I want him to come to

me. I want to say that I have fallen in love with him and that I no

longer want to live without him, that I can’t live without him. But

he won’t let me say any of that. He is also crying now. Then he

simply kisses me one last time and walks out of my hotel room,

leaving me all alone.

After Omar left her room at the Omayyad Hotel, Shultz stepped out on her balcony and saw him pause at the intersection, looking back at her.

What followed her to New York City from Damascus was anything but a normal life. She felt shell-shocked, as if she had been in an active war zone, but she couldn’t shake the twenty-four hour “all-Iraqi-all-the time loop.” She lay on her couch as if in a dream, all the individual stories she had heard coming at her: “All the kidnappings and killings, all the horror and heartbreak, all the torture and terror, all the skukrans [thank you] and shawarmas[best sandwich in the world].” She knew, of course, they were not a dream—these stories—they were all too real. But in their reality, perhaps, in this pre-Damascus awakening, who is to know how they affected her openness to fall for the one Iraqi refugee who turned her life upside down?

Omar was not responsible for her deeper understanding of how the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and other militant organizations, such as the Sunni Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI, which morphed into the Islamic State), had torn apart the fabric of Iraqi lives. Shultz understood this tragedy before she met Omar. Still, there was a correspondence between the pre- and post-Damascus periods, with one difference: The latter would ensue in the physical safety of a long-distance love affair, but the feelings were as powerful and deep as any she had experienced in her life, enclosing her in a want-to-believe universe. Just as her interviews with the Iraqi refugees shook her New York world outlook, so her post-Damascus journey with Omar would confront her as profoundly, even more so. What did it mean?

With Omar thousands of miles away, their three-year “intercontinental Internet relationship” was cobbled together through the technological innovations of the twenty-first century: IM, email, cell calls, and video. Needless to say, it was not a simple or easy relationship. It had its peaks, and, of course, its valleys, and sometimes the valleys did not offset the peaks. Schultz wrote her first email to Omar on October 21, 2009. This correspondence continued for three years: more texts, emails, cell calls, and video. Anyone who has carried on a long-distance relationship via this technology knows how fraught it can be with dropped messages and calls and paused video, but more often, they can cause human misunderstandings fretted over until the next message or call.

Schultz struggled to understand the relationship, if there was any long-term good that would come of it and if marriage was in the cards. She second-guessed herself: Was it worth it, this long-distance affair with a refugee? Or, maybe Omar was the wrong Iraqi, as he himself told her. She tried to fathom how Omar felt about her, what she meant to him, why they had fallen for each other. She replayed their conversations and reread his texts. She tried to make sense of the long intervals between their communications. Did he love her? She wondered if she should see a therapist.

By March 2010, she was well into editing the play she had written about the millions of Iraqis stranded in the Middle East—and Omar. Although he disappeared for weeks at a time, she couldn’t keep him out of her mind, like the love song goes, in spite of the back-and-forth nature of their tech embrace. He wanted to see her on camera with her hair down. They engaged in sexy flirting. Omar called her “habibti.” She felt close to him when he said that word. At her favorite coffee place, she got lost in “Omarland,” where she dreamed up the idea of selling Omar’s art in New York City. She would go into the refugee art business. She would get close to him through his art.

In August 2010, Schultz performed a public reading of her play. Was she up for dramatizing “the whole story so that the world may know?” Later that month, Omar asked her to come to Damascus, his first invitation to visit him. Schultz began to apply for a visa. Sometime between August and September—Schultz doesn’t say—Omar disappeared again. When she heard from him, he wrote in a text: “Kim. Can’t come online today. Sorry. I met Iraqi girl. I think I love her. Am happy.” Schultz visited a monastery. She was alone with the monks for the weekend—to study her soul.

Fast forward to 2013. Omar had made it to Canada and was living in Vancouver. During those intervening years, she lived her frustration, anger, hurt, and love every time she performed her play. When she texted him that she wanted to visit him in Syria, he responded that Syria had become too dangerous and he was going back to Baghdad. Trying desperately to get him out of this perilous situation and the ambient loneliness that he suffered daily, Shultz thought about: an artist visa (hard to get); the U.S. resettlement program (backlogged); the International Office of Migration (IOM) (paperwork expired); and a K1 visa— a fiancé visa—best chance.

They could get engaged and maybe they would get married, she hoped, and definitely within the stipulated three months timeframe. Omar liked the idea, at first. She proceeded to hire a lawyer, fill out the paperwork, and wait. In the meantime, he applied for a Canadian resettlement visa, to hedge his bets. In early 2012 Schultz received the Department of Homeland Security approval for the fiancé visa petition 1129F. Schultz called Omar, excited, but he brushed her off, he was sleeping, could she call another time. On February 25, 2012, Omar sent her an instant message, telling her it was better if he waited for a Canadian visa. What he didn’t tell her at that time was that he had agreed to an arranged marriage, a week before the K1 visa came through. His family wanted him to marry an Iraqi woman. It was for the best.

Why didn’t she walk away from Omar and their international Internet relationship? It was a question she didn’t have easy answers for. Ten months after the K1 visa was approved and three months after her last Internet communication with him, Omar was resettled in Canada. She went to Mexico for three months and grieved her loss: “With our shared moon starting to climb the sky, I cry for what could have been, for what I thought was. I cry because I am not with Omar in Canada right now . . . I cry for what has been lost, never to be found. I cry for all the Iraqis broken, still trapped in dangerous lands, not their own.”

After three rejected visas, “a revolution, a resettlement, an engagement,” Shultz found closure with Omar in Vancouver. When they saw each other for the first time in over three years, it was like a scene in a movie when the woman sees her lover from a distance, looks again, sees the man she loves walking toward her. He sees her, begins to laugh and walks closer as tears well up and they embrace. He says, “Habibti,” and they both are crying. And then, in three short days, Omar is gone, “three years, two visas and one fiancé later.”

In the Epilogue, Shultz considers what those three long years were about. Why did she persist in this long-distance relationship? If he didn’t need her, as it seemed, what was the relationship really about? As with most love stories, some are forever and some go awry, and some are mysterious and unfathomable. Nevertheless, Schultz searches for meaning. It is a love story, she is certain of that, but it is also a redemptive story. For her? For him? What she knows is that they are physically safe and lucky to have found each other. Their ending allows them to begin anew. The refugees she met in Iraq don’t get an ending; they belong to the “Diaspora of a people and their culture.” What she does know is this: She couldn’t let go of all the Iraqis she interviewed—their stories, their sadness, and their loss. Most of all, she couldn’t let go of the Iraqi man she fell in love with, Omar, whom she would always love.

For Kim Schultz, there would always be pre- and post-Damascus awakenings. For you, the reader, there will always be the book Three Days in Damascus that you won’t want to leave, even after you come to the ending. There will always be a beginning around the corner.