Note to the Reader: This review was written before the 2012 Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to the renowned Chinese writer Mo Yan on October 11, 2012. The state-run news media praised it as an affirmation that China’s cultural accomplishments had caught up with its “economic prowess.” The Chinese government’s response to Mo’s Nobel award stands in sharp contrast to the government’s reaction in 2010 when the dissident Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Then, the government called it a “Western propaganda tool intended to insult and destabilize the ruling Communist Party.” ( See NY Times article, October 2012) A day after Mo won the Literature award, he said, “I hope he [Liu Xiaobo] can achieve his freedom as soon as possible.” This is unlikely, as the following review will show.

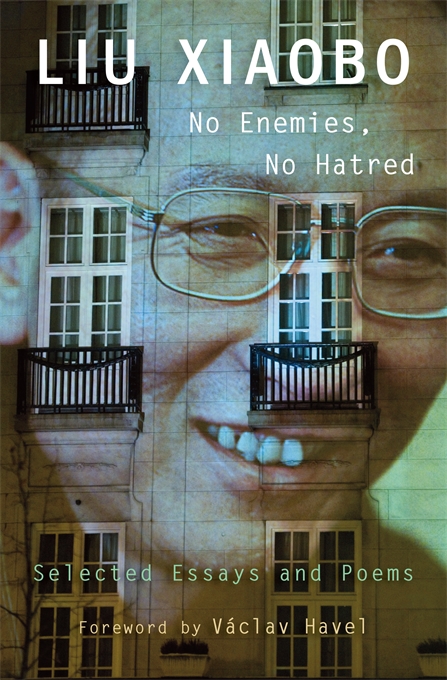

An unusual sight appeared on the streets of Oslo, Norway, on December 10, 2010, the day of the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony. As a torch parade passed by the Grand Hotel in honor of the Chinese human rights dissident Liu Xiaobo, the 2010 recipient of the Peace Prize, his portrait was projected onto a wall of the hotel.

From the balcony, Nobel recipients usually wave to passersby. In 2010, the recipient was nowhere to be seen: The portrait on the wall was a stand-in for Mr. Liu. On December 25, 2009, he had begun serving an eleven-year sentence in Jinzhou Prison in Liaoning Province for committing “the crime of incitement to subvert state power.” The Chinese government had refused to allow him, his wife, or any family member to travel to Oslo to receive his medal and the 1.5 million dollar prize. At the ceremony, the Nobel Committee placed the prize medal inside a small box, “and the prize certificate, in a folder that bore the initials ‘LXB’” on an empty high-backed chair on the stage. A large portrait of Liu stood in his stead. He was the first Chinese person living within Mainland China to receive a Nobel Prize.

When the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced the award on October 8, 2010, prison officials informed Liu that he had won the Nobel Peace Prize. Two days after the announcement, his wife, Liu Xia, was allowed a one-hour visit with him. Remembering “those souls of the dead” who were brutally gunned down at Tiananmen Square, he wept, Liu Xia reported. He told her “the award commemorates the nonviolent spirit in which those who died fought for peace, freedom, and democracy.” Liu Xiaobo had never recovered from what he witnessed on June 3-4, 1989, in Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing. Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader of the Communist Party of China, and the ruling hard-liners in the Chinese government had declared martial law on May 20. On the evening of June 3, the People’s Liberation Army entered Beijing in military convoys and shot and killed anyone blocking its path to the Square. No one knows how many civilians died.

The Chinese government, not happy when it learned Liu Xiaobo was one of 237 names submitted to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, warned the Committee that such an award to Liu would damage Sino-Norwegian relations. Support for Liu’s nomination was strong: Several Chinese dissidents had signed a letter supporting his nomination, as did Václav Havel and the former Nobel Laureate Desmond Tutu for his “unflinching and peaceful advocacy of reform.” The philosopher Xu Youyu, a signatory to the human rights manifesto “Charter 08” that got Liu into trouble with the authorities for the fourth time and for which he was accused of instigating subversion of state power, wrote in an article in support of Liu: “His activities in 1989 can be seen as formative in the entirety of his following writings and other works, characterized by an unwavering bravery and refusal to back down in the face of danger and suppression, by the pursuit and defence of human rights, humanism, peace and other universal values and, finally, adherence to the practice of rational dialogue, compromise, and nonviolence.” (The Guardian, October 8, 2010). When the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced on October 8, 2010 that it had awarded the Peace Prize to Liu “for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China,” the Chinese government censored the Internet, television, and print media inside China; arrested celebrants; put Liu Xia under house arrest; and threatened several foreign diplomatic missions with consequences if they attended the award ceremony on December 10. Calling Liu Xiaobo a “criminal” who had violated “Chinese law,” the foreign ministry said the award “runs completely counter to the principle of the prize and is also a blasphemy to the peace prize.” Xu, the philosopher, stated, on the contrary: “The prize was compensation for the ‘enormous sacrifice’ Liu had made in the pursuit of democracy and human rights in China.” (The Guardian, October 8, 2010).

The Chinese government cannot be happy, either, that Liu Xiaobo now has a global readership, thanks to the effort of Perry Link, a Sinologist at the University of California- Riverside, who translated and published in The New York Review of Books “China’s Charter 08,” the manifesto that calls for replacing one-party rule in China with a democratic system of government based on the universal principles of human rights. Along with editors Tienchi Martin-Liao and Liu Xia and thirteen translators, Link has given the English-speaking world a gift: We can sit in the privacy of our homes and read the trenchant, passionate, and morally persuasive writings of Liu Xiaobo in No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems— released in January 2012—and be moved to understand the People’s Republic of China from the perspective of a prisoner of conscience. Liu Xiaobo—poet, essayist, academic intellectual, political dissident, human rights activist—is the author of hundreds of essays and seventeen books, and, as Link writes in the Foreword to No Enemies, No Hatred, “to peruse this large oeuvre and select essays that reflect the breadth of his interests and the range of his erudition is no easy task.” Most of the essays in No Enemies, No Hatred are from the period between 2004 and 2008, and reflect, in the service of freedom of speech, how words followed by action can change the direction of a country.

Liu, now 56, did not begin his career as a political dissident and the author of essays criticizing the Chinese government for its one-party rule, corruption, lies, and violence. Before Tiananmen, he was a “public intellectual” and distinguished professor of Chinese Literature at Beijing Normal University, traveling abroad as a visiting scholar and writing books and essays about literature and culture. After Tiananmen, as the essays in No Enemies, No Hatred indicate, he penned articles and commentary about political reform in China: changing a regime by changing a society (the title of one of his essays) from the bottom up, and ultimately transforming a dictatorial government into one guided by the rule of law, democracy, and the universal principles of human rights. Consequently, Liu was a perennial suspect—monitored, arrested, and imprisoned.

His first arrest came two days after the massacre in Tiananmen Square, on June 6, 1989. The authorities accused him of being a “black hand” behind a “counterrevolutionary riot,” and he spent eighteen months in Qincheng Prison in Beijing for participating in the student-led pro- democracy movement that changed his life. In May 1995, he was arrested for the second time and placed under house arrest “inside a large courtyard at the base of the Fragrant Hills outside Beijing” for eight months, presumably for releasing the petition, “Learn from the Lesson Written in Blood and Push Democracy and Rule of Law Forward: An Appeal on the Sixth Anniversary of Tiananmen.” No reason was formally given for this arrest. On October 8, 1996, he was arrested for the third time and “sent for three years to a reeducation-through-labor camp in Dalian, in his home province of Jilin.” (Most of the poems included in No Enemies, No Hatred were written and dedicated to his wife during this period at Dalian.) The reason for this third arrest: publishing a statement with a well-known dissident Wang Xizhe “on the sensitive topic of Taiwan’s relations with mainland China.” Liu and Wang had included the following sentence in the statement: “ ‘Is the government of the People’s Republic of China the only legitimate [Chinese] government? In our view, it is both legitimate and not completely legitimate.’” It was during this time in Dalian, Link writes, “that Liu Xiaobo seems to have formed his deepest faith in the concept of ‘human dignity,’ a phrase that has recurred in his writing ever since.”Almost twenty years after Tiananmen, on December 8, 2008, the Beijing police closed in on Liu Xiaobo and arrested him. He was taken to a secret location two days before “Charter 08” was formally announced on the sixtieth anniversary of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights—December 10, 2008. He was placed under “residential surveillance” on December 9, 2008, arrested on June 23, 2009, and sentenced to eleven years in prison on December 25, 2009. He was an ex-professor punished “merely for expressing different political views and for joining a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher” who “lost his right to teach, a writer” who “lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual” who “could no longer speak openly.” When he wasn’t in prison, Liu defied the authorities at every turn, learning how to use the Internet in the late 1990s, evading the “Great Firewall,” and supporting himself and Liu Xia as a freelancer. Being censored in China, he found willing publishers in the foreign media—Hong Kong, Taiwan, the United States, the United Kingdom.

It cannot be overstated how the events of June 1989 affected Liu and altered the trajectory of his life: Tiananmen put him “on the road to political dissidence.” When the pro-democracy movement began in April 1989 in Beijing and spread to other cities in China, Liu was a visiting scholar at Columbia University. Sensing the historical moment, he felt an urgent need to return to Beijing to participate, and with the students, to demand of the Chinese government economic reform, freedom of the press, and political liberalization. On June 2, Liu and three friends began a hunger strike: One of its goals was “the establishment throughout society of popular self-governing organizations that can gradually give shape to popular political forces that will serve as counterbalances to the central governing authority.” The hunger strike was cut short when military tanks entered the Square and killed people indiscriminately. Link writes in the Foreword: “…Liu negotiated with the attacking military to allow students a peaceful withdrawal. It is impossible to calculate how many lives he may have saved by this compromise, but certainly some, and perhaps many. After the massacre, Liu took refuge in the foreign diplomatic quarter, but later came to blame himself severely for not remaining in the streets—as many ‘ordinary folk’ did, trying to rescue victims of the massacre. Images of the ‘souls of the dead’ have haunted him ever since.”

In the statement “Using Truth To Undermine A System Built on Lies” (originally published in Zhengming, June 2003) to the Chinese Democracy Education Foundation in San Francisco, which had given Liu one of its awards “for outstanding activism in the promotion of Chinese democracy,” Liu describes what happened on the night of June 3 and morning of June 4: “I was a participant in the 1989 movement and observed how, in that dark night and early dawn, it was sliced by bayonets, pierced by bullets, and crushed by tanks. The glinting tips of the bayonets still stab in the recesses of my memory. As one of the survivors, I see before my eyes two things—the souls of those who died for a free China and the violence, the lies, and the bribery of the killers—and I am haunted by the grave responsibility of being still alive. I do my best to make every word from my pen a cry from the heart for the souls of the dead. I use my memory of their graves to combat the Chinese government’s pressure to erase memory; my searing desire to atone for having survived helps me resist the temptations to join the world of lies.” It is impossible not to sympathize with Liu’s pain and to understand his survivor’s guilt. More difficult, however, is absolving the Chinese government of its brutality at Tiananmen. Liu’s memories of Tiananmen help to explain his commitment to nonviolent resistance against the Communist regime. In essay after essay, with moral clarity, knowledge, and insight, Liu elucidates the conflict between the people and the corrupt dictatorship. In the essay, “So Long As Han Chinese Have No Freedom, Tibetans Will Have No Autonomy,” (originally published in Guancha, April 11, 2008) for example, he understands the problem between China and Tibet as one between dictatorship and freedom: “We must be clear that the roots of the crisis in Tibet are the same as the roots of the crisis in all of China. The conflict between central rule and the ‘high level of autonomy’ that Tibet is seeking is in essence a conflict between dictatorship and freedom”—“a struggle between two political systems.”

The conflict between “dictatorship and freedom”—two political systems—is a subtext in the essay “Behind The ‘China Miracle,” (originally published by the BBC, November 4, 2008). In the 1990s after Tiananmen, Liu explains, “Deng Xiaoping was attempting to recoup his authority and to reassert his regime’s legitimacy after both had melted away because of the massacre. He set out to build his power through economic growth, justifying the move with the slogan ‘development is the bottom line.’” Corruption followed: The economy flourished, powerful officials made huge amounts of money, the economy boomed. Everyone called it a “miracle,” and Liu agrees—it was. China became a global economic partner, and its economic success continues today, significantly raising the standard of living for hundreds of millions of Chinese and quadrupling the per capita income. The problem, as Liu sees it, is one of corruption and power: “The economic ‘miracle’ happened because of marketization and privatization. Here ‘marketization’ does not mean creating markets under the rule of law; it means marketization of political power, that is, allocating capital and other resources through political authority. And ‘privatization’ has been neither lawful nor ethical; on the contrary, it has meant a robber baron’s paradise, a free-for-all.” The result: An inflated Communist Party, not by Marxist ideology which “has fallen by the wayside,” but by the magnitude of “sheer opportunism by which any action can be justified if it upholds the dictatorship or results in greater spoils.” Thus, the political reform in the 1980s, and its combination of “free-thinking intellectuals, passionate young people, private enterprise that attended to ethics, dissidents in society, and a liberal faction within the Communist Party” no longer exists. In its place lies systemic corruption, an unjust society, moral decline, a squandered future. The Party as power, the Party as supreme—the struggle between dictatorship and freedom.

One could say that Liu Xiaobo’s credo is “the living of an honest life” in “a quest for human dignity.” Even as the Chinese government represses him, he strives to stay true to this credo, always keeping the honesty, dignity, and welfare of “ordinary folks” in mind. Nowhere in any of the essays in No Enemies, No Hatred does he advocate revolutionary change in

China. Believing it would hurt “ordinary folks,” as happened at Tiananmen, he argues for “progressive democracy,” one that empowers through “moral standards, intellectual vitality, social concern, and political participation.” In one of the six articles adduced at his trial in December 2009, “To Change A Regime By Changing A Society,”(originally published in Guancha, February 26, 2006) he writes: “We must face squarely, with no illusions, the fact that the dictatorial system will be with us for some time…. In the push-and-pull between the ruling authority and civil society, official policies will change from time to time, but our own unchanging priority must always be to encourage and support the rights-defense movement and to protect the independence of civil society.” He believes change will happen only from the bottom up, and he identifies three factors that will move China along the “road to a free society”: “the growing self-awareness among the people,” a popular rights-defense movement, and pressures from below on the regime. As in so many of the essays, Liu rephrases again and again the necessary conditions for a free China. For example, in the essay “Imprisoning People For Words And The Power Of Public Opinion,” (originally published in Ren yu renquan, March 2008) he believes change will come, not from heroic acts, but from “the low-key, practical ways in which people everywhere keep making small differences.” They “do what they can in their immediate environments,” he writes, “aware that the political regime is not going to change any time soon….” Perhaps Liu has in mind the small differences people make in their environment when they either do not believe the lies they are told by an authoritarian regime or when they themselves do not tell lies.

Not telling lies, not disseminating them, and not believing them is integral to Liu’s living an honest life. Even as he personally has fought against the Communist regime’s oppression, Liu grounds his writings not in angry recriminations, but on truthful, reflective criticism—on not telling lies. In the essay “Using Truth To Undermine A System Built On Lies” (mentioned above), Liu writes: “Moral prohibitions against lying are fundamental in the ancient texts of all the world’s cultures. For the people in this world who still live under dictatorships, resistance to lies continues to be the first step in the pursuit of freedom from fear and coercion, which is something every human being yearns for. Dictatorships need lies and violence to maintain the coercion and fear upon which they depend…. No single person, of whatever status, can fight back against regime violence alone, but the refusal to participate in lying is something that every person can accomplish. To refuse to lie in day-to-day public life is the most powerful tool for breaking down a tyranny built on mendacity.”

Refusing to lie, but also refusing to believe the lies a tyrannical regime tells its people, is a nonviolent act. Link notes that Liu has studied the nonviolent practitioners of the twentieth century. These include Mohandas K. Gandhi and Václav Havel, but also, of course, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who led the struggle against racial segregation in the 1950s and 1960s in the United States. Surely, Liu would have read the following words from Dr. King’s now-famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which Dr. King wrote to answer his critics: “Moreover, I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”Like Dr. King, Liu reveals in the essays in No Enemies, No Hatred that he too believes in “an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” As the above quote from his essay on Tibet shows, Liu sees the necessary reciprocity between China and Tibet: They will be free together. And just as Dr. King writes that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” so too Liu condemns the violence of the Communist regime against one person as an injustice against all. In one of the most forceful condemnations of the regime’s behavior toward its people, he writes in the essay “A Deeper Look Into Why Child Slavery In China’s ‘Black Kilns’ Could Happen” (originally published in Ren yu renquan in 2007 and one of six articles adduced at his trial): “The reason the regime is so coldhearted is not that the human beings in it are all coldhearted. The problem is the cruelty of the authoritarian system itself. This kind of system cannot adapt to respect life or uphold human rights. A ruling group that makes maintenance of its monopoly on power its first priority can never turn around and put the lives of people—even children—in a higher position. In the end it is because the system does not treat people as people that such hair-raising atrocities can come about. Authoritarian power is as cold as ice. It obliges people to focus on power and power alone, and this makes feelings of human warmth impossible.”

As with the writings and action of the practitioners of nonviolence and any number of organizations that teach and practice nonviolence, Liu’s writings embody the power of words as he wages his nonviolent struggle against an authoritarian government. As one would expect, the Chinese government did not find Liu’s writings valid or defensible. On the contrary, they found them subversive, slanderous, and illegitimate. In 2009, Branch No. 1 of the People’s Procuratorate of Beijing indicted Liu Xiaobo “with the crime of inciting subversion of state power,” and on December 10, 2009, Branch No. 1 “delivered its Indictment” to Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court for prosecution. The Indictment begins as follows: “The Indictment from Branch No. 1 of the People’s Procuratorate of Beijing charges that Defendant Liu Xiaobo, because of his dissatisfaction with the People’s Democratic Dictatorship and the socialist system in our country, began in 2005 to use the Internet to post subversive articles….” The Indictment lists the six articles (two are included in No Enemies, No Hatred), the foreign websites that published them, and quotations from each of the articles. It then states: “…between September and December, 2008, Defendant Liu Xiaobo colluded with others to draft and concoct Charter 08…and that, after collecting more than 300 signatures on it, Liu Xiaobo used email to send Charter 08 and the signatures for public posting on the foreign websites of Democratic China, Independent Chinese PEN, and other foreign websites.” The Indictment considers Liu’s writings and endorsement of “Charter 08” crimes and his criminal behavior “severe.”

The Chinese government did not like “Charter 08.” 303 people had signed it when it was formally announced on December 9, 2008, and 12,000 signed it after it was posted on the Internet. In the Foreword to “Charter 08,” the authors accuse the Chinese government of having “many laws, but no rule of law” and “a constitution but no constitutional government.” Among the universal principles the authors endorse in “Charter 08” are “freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom in where to live, and the freedoms to strike, to demonstrate, and to protest….” What agitated the Chinese government, however, was not only a call to reform the present authoritarian system but, also, an end to one-party rule. It would be impossible for the Chinese government, as presently structured, to maintain its authoritarian character if the nineteen recommendations listed in “Charter 08” were to be implemented. These recommendations include a new constitution, separation of powers, an independent judiciary, guarantee of human rights, election of public officials, and the freedoms mentioned above. As the leading signatory on “Charter 08,” Liu was the main target, and the Chinese government wasted no time in picking him, incarcerating him, prosecuting him, and sentencing him to eleven years for his “criminal behavior.” The Court’s “Judgment” reveals the threat of Liu Xiaobo’s writings and nonviolent resistance: “It is the judgment of this court that Defendant Liu Xiaobo, with the goal of overthrowing the state power of the People’s Democratic Dictatorship and the socialist system of our country, took advantage of the Internet with its features of rapid transmission, broad reach, large influence on society, and high degree of pubic notice…. His actions have constituted the crime of incitement to subvert state power, have persisted through a long period of time, and show deep subjective malice. The articles that he posted, which spread widely through links, copying, and visits to websites, had a despicable influence. He qualifies as a criminal whose crimes are severe and deserves heavy punishment according to law.” On December 25, 2008, Liu Xiaobo was sentenced to eleven years in prison and “the deprivation of political rights for two years.”

Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court did not accept Liu’s defense when he presented it at his trial on December 23. After he began to read it, he was cut off after fourteen minutes— equal to the time the prosecution took to present its case against Liu. In his final statement at his trial, “I Have No Enemies,” he states that he is innocent of the charges against him and, in any case, they are unconstitutional. A masterpiece, “I Have No Enemies” transforms words into deeds, beliefs into action. His eloquence is striking and his moral clarity unbending: “I wish, however, to underscore something that was in my ‘June 2nd Hunger-Strike Declaration’ of twenty years ago: I have no enemies, and no hatred. None of the police who have watched, arrested, or interrogated me, none of the prosecutors who have indicted me, and none of the judges who will judge me are my enemies. There is no way that I can accept your surveillance, arrests, indictments, or verdicts, but I respect your professions and your persons….

“Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people (as the experience of our country during the Mao era clearly shows.) It can lead to cruel and lethal internecine combat, can destroy tolerance and human feeling within a society, and can block the progress of a nation toward freedom and democracy. For these reasons I hope that I can rise above my personal fate and contribute to the progress of our country and to changes in our society. I hope that I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Liv Ullmann, the Norwegian actress, read “I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement” in its entirety at the Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony on December 10, 2010. The portrait of dissident Liu Xiaobo projected onto a wall of the Grand Hotel in Oslo, Norway, on the day of the ceremony graces the cover of Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems—the only book of his writings published in English.